Tapping Into a Deeper Trust

Sacred waters still flow (even from humble spigots)

My sense of social and environmental trust has cratered like never before during the past five or so years. And I haven’t liked the experience at all. True, I’m fortunate in that I still trust my close friends and family completely. But when it comes to the wider world — American society and culture, our leaders and institutions, my hometown of Chicago, strangers on the street, even the natural environment — I don’t trust any of it nearly as much as I used to. The wrenching events of recent years have decimated that once-default setting. And I’m certain that it won’t come back anytime soon — or more likely, ever.

I used to have an easy faith that at least a solid preponderance of our leading institutions, experts, and authorities could be trusted most of the time. I used to imagine myself as a small part of a much bigger progressive liberal project that shared a common commitment to the furtherance of American democracy. I used to assume that the basics of the natural environment had a bedrock predictability: Growing up in the Midwest, the changing seasons of Summer, Fall, Winter, and Spring had always turned in a dramatic and even severe, but nonetheless comfortingly regular rotation.

None of this holds true anymore. I’ve lost trust in American institutions. The political tradition I used to identify with has been subsumed by a different paradigm that I don’t like. And the new normal in what used to be my stolidly predictable climate zigzags from being alarmingly warm at Christmas to discomfortingly cold on Memorial Day. What used to seem dependable and predictable is now neither.

Remapping the Mental Terrain

Decades of previous life experience have prompted the part of my brain that wants to stick with its familiar patterning to insist that none of this is how it’s “supposed” to be. It’s all wrong. It’s crazy! I’ve asked myself repeatedly: Is it even really happening? Maybe my own perceptions are wildly off. Maybe nothing’s changed as much as I think. Maybe I’m being paranoid and need to get a grip.

But over time, I’ve gotten used to it. Now, I’m much more comfortable in my belief that these perceptions are essentially right. In fact, I felt strangely vindicated the other day when I read a recent New York Times story on how the Earth veered off its old 20th-century axis sometime in the early 2000s. I didn’t feel it at the time. But now, looking back, on a metaphorical level, that seems exactly right.

Slowly but surely, I’ve come to the conclusion that the mental map of the world I’d developed over the prior course of my life has in many ways become obsolete. Sure, a good part of it still works fine. But far too much of it doesn’t for me not to notice.

I’ve come to realize that I’d better start recharting a substantial part of this cognitive terrain if I want to have a more accurate representation of the world as I now perceive it. Which I do. Because walking around with a map in your mind that you sense is no longer trustworthy is draining, dispiriting, and not infrequently anxiety provoking and/or depressing. And that’s not a good way to live.

Having a mental map you feel you can rely on is important if you want to negotiate the world with a sense of trust. The more that there’s a disjuncture between what your brain says “should” be true and reality as you’re actually experiencing it, the more the mistrust swamps you. Rather than feeling confident that you know what’s what and can figure out how best to navigate it, you’re uncertain, disoriented, and perhaps even lost. That’s disempowering and potentially debilitating.

Without some reasonable sense of what’s true and what’s not, there’s no way to judge what’s accurate, meaningful, or even safe. As a result, more and more of the world starts to look nonsensical, meaningless, and/or threatening, regardless of whether that’s really the case. The fact that there’re plenty of good reasons to feel so mistrustful today doesn’t change the fact that this poses a serious problem.

Navigating the world with such pervasive mistrust threatens to break our sense of connection — to each other, to our deeper selves, to nature, to our sense of the sacred, and even to life itself.

We see the negative consequences of this profound breakage of trust and connection all around us. American society is riven with resentment, envy, fear, hatred, scapegoating, cruelty, and violence. Countless people are suffering from terrible physical and psychological health at levels ranging from concerning to catastrophic. Sometimes it feels like a vortex of demonic energies has descended and is moving across the land like a tornado, chewing up vulnerable people and places in its path. Of course, there are still plenty of pockets of tranquility and times of seeming “normalcy.” Regardless, the deeper vibe remains threateningly dystopic.

Faith and Trust

Living well in such an environment requires cultivating a deeper trust. One way to do this is to tap into resources with strong historical roots, such as art, myths, philosophies, religions, and spiritual practices that have stood the test of time and that you find positive and inspiring. Such traditions remind us that developing life-affirming ways to steer through difficult times used to be a primary theme of human cultures. This is something we’ve largely lost, to our individual and collective detriment.

The classic formulation of Hebrews 11:1 comes to mind: “Now faith,” the scripture tells us, “is the assurance of things hoped for, a conviction of things not seen.” Tellingly, the Complete Jewish Bible translates this verse a bit differently:

Trusting is being confident of what we hope for, convinced about things we do not see.

In this text, “trust” has been chosen as the best English translation instead of the more commonly used “faith.” I find this thought-provoking: What do these differing interpretations suggest about the relationship between “faith” and “trust”? And what might those words signify in this context?

To have faith is to trust that certain things are reliably true — even, as this passage underscores, when we can’t see them. Conversely, to trust is to have faith that certain things are reliably constant, even when there may be confusion, difficulty, or pain in the present moment. The bottom line is that to trust that we can tap into the deeper goodness of life regardless of what present circumstances may be is to have faith, whether one is a traditional religious believer or not.

Of course, this isn’t always easy. But isn’t that the point, really? “Faith is the evidence of things not seen.” To commit to a deeper level of trust in life is to manifest the faith that is its own evidence of truth, regardless of what we may or may not see in the world around us.

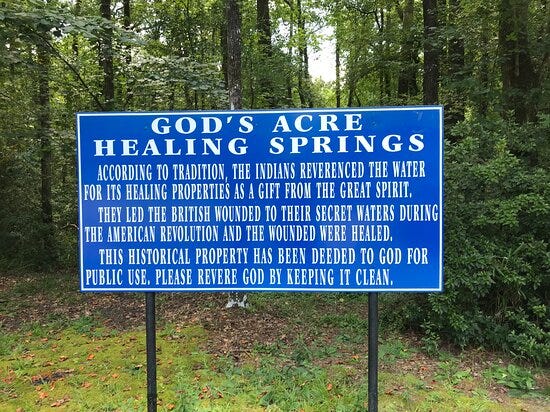

God’s Acre Healing Springs

While visiting a friend in coastal South Carolina last week, I asked a man who’d grown up in the area what he’d recommend seeing. After a bit of throat clearing (“you may not like what I like,” he replied. “Try me,” I countered), his first suggestion was God’s Acre Healing Springs in (somewhat) nearby Blackville. As soon as I heard about it, I knew that I wanted to go.

Happily, my friend was as intrigued by his suggestion as I was. And so soon enough, off we went, driving almost two hours through the South Carolina Lowcounty, an open, green, and lightly rolling rural landscape periodically punctuated by modest homes, trailers, churches (lots of churches), and some very very small towns.

This trip to God’s Acre Healing Springs was what first got me thinking about trust. Because it was remarkable to be somewhere that evidenced such a stable and cohesive sense of social, cultural, governmental, environmental, and even (quite explicitly) sacred trust. The contrast with the pervasive sense of mistrust I’d been grappling with back home in Chicago was stark. And welcome. It helped me see more clearly some of what I’d been missing. (If you’re interested, you can watch my very amateurish 30-second video of our visit here.)

God’s Acre Healing Springs is the sort of place that my friends who’ve always lived in the cosmopolitan urban North and never visited the off-the-beaten-path rural South would have an extremely hard time wrapping their heads around (assuming they’d even want to try, which is not always the case). Here’s how the South Carolina Picture Project describes it:

God’s Acre Healing Springs are located behind Healing Springs Baptist Church in Blackville on land that has the unusual distinction of being deeded to God. Their mineral waters flow from nearby artesian wells, and the springs have been a source of folklore spanning centuries.

. . . Stories of the springs’ healing power were popularized during the American Revolution. Legend holds that four British soldiers were severely wounded in a nearby battle at Windy Hill Creek. They, along with two men ordered to bury them when they died, were rescued by Native Americans, who took them to the springs. Six months later, all of the soldiers returned to their post in Charleston, crediting the springs’ water with their miraculous recovery.

. . . The land passed through many hands before it was eventually purchased by Lute Boylston. In 1944, Mr. Boyston decided to deed the land to God so that everyone could enjoy the spring’s healing powers.

Centuries later, South Carolinians continue to hold the site sacred, and many people – of all races and socioeconomic classes – travel hours to collect water from its humble spigots.

There are so many ways in which the everyday reality of this sacred site confounds the dominant sensibilities of my progressive Blue State urban bubble, it’s hard to know where to start.

But to begin with: There’s the fact that everyone in the area — including the local county government — easily accepts that the land has been officially owned “by God” since 1944. Reportedly, there’s a deed to this effect on file in the nearby Barnwell County Courthouse. So OK. How does that work, exactly? I have no idea. But it does.

Then there’s the glaringly, blaringly politically incorrect legend about how “the Indians” saved the lives of some wounded white soldiers by taking them to their sacred healing site. This would not go over at all well in Chicago, where our city government has been busily reevaluating what to do about our many historical monuments that don’t conform to today’s officially sanctioned sensibilities. (Side note: In certain cases, corrective change seems entirely warranted. All too often, however, this drive to rewrite history is a waste of public resources at best.) Needless to say, any depictions of Native Americans, no matter how beautiful or inspiring, are on the potential hit list.

While I’m an outsider and can’t say for certain, I have a strong sense that such issues would be written off as completely missing the point by the racially diverse set of Southern locals who regularly frequent God’s Acre Healing Springs. What matters there are the healing waters. What matters is that the land is entrusted to God. What matters is that everyone follows the admonition on the signage to “Please Revere God by Keeping It Clean.”

Within this regionally shared framework of cultural meaning, it only makes sense that everyone, regardless of everything (most certainly including our now standard set of political identity markers), should have equal access to this sacred site (provided, of course, they respect it).

That said, I must admit that as a visitor from a very different part of the country who’s always lived in a very different culture, I definitely thought twice before deciding to drink the water that burbles continuously out of its uber-basic T-shaped metal spigots. Was this “healing water,” I wondered, really being tested regularly? Was it really wise to simply assume that it’s uncontaminated and safe? Was I really just going to take God’s Acre Healing Springs at face value, fill up my stainless steel water bottle, and drink?

It was a quick decision. My answer was “Yes.” For sure. Of course I would. And I did. It tasted like good, clean water. And maybe it was just my imagination, but as it went down, I felt a certain energetic buzz.

Ever since, I’ve felt happy to have had the chance the drink the healing waters right at their source — and to have taken that opportunity. I trusted God’s Acre Healing Springs. And I trusted the confluence of events that had led me to be there.

Both felt really good.

Love this! Another one so well put at so many levels! I assume the SC friend you mentioned is Vicki.

Thank you for sharing, Carol. You describe much of what I’ve been feeling for several years. You are fortunate to still trust your immediate family and friends. It’s particularly difficult when that is gone.